Kumar Paudel

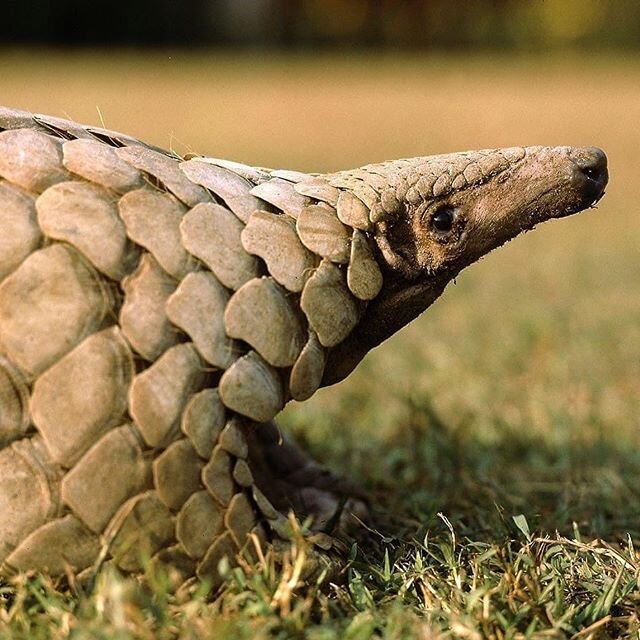

Many people around the world know what a pangolin is. Pangolins have garnered global attention as the most trafficked mammal in the world. In the past year, pangolins came into the spotlight because of widespread suspicion that a pangolin served as an intermediary source of COVID-19. Wildlife conservation conferences, wildlife trade reports, and important policy documents hardly miss pangolins these days – here they have focused attention. However, the frontline authorities and communities living with the pangolins know very little about them.

Pangolins, known as unique scaly anteaters, are on the verge of extinction due to poaching and habitat destruction. Experts have warned that some pangolin species, including Chinese pangolins, could go extinct if the threats they face continue. Nepal is home to two pangolin species: the Chinese pangolin and the Indian pangolin; both species reside outside protected areas for the most part. As a conservationist based in Nepal, an incident that occurred a few months back made me realize how little we know about pangolins, especially the local communities who share their habitat and the teams who deal with their rescue and release.

In the first week of November 2020, a Chinese pangolin was seized near Kathmandu, Nepal. It was caged in a small wooden box but still breathing. The next day I received a call for help from the Division Forest Office when the seized pangolin gave birth to a baby. They were unsure of how to care for the mother and baby pangolin. The mother pangolin was still enclosed in the small wooden box, and a few people were trying to find ways to help the baby. However, neither the officials nor researchers like me were sure of how best to proceed to help them both.

Pangolin seized by Nepal Police in Nov 2020 in Bhaktapur which gave birth to a baby pangolin in the police custody. Photo: Kumar Paudel/Greenhood Nepal

Newly born pangolin baby at police custody in Bhaktapur Nepal, the mother pangolin was seized while illegally transporting from Dhading district. Photo: Kumar Paudel/Greenhood Nepal

To start, I checked with the only zoo in Kathmandu, and was informed they had no capacity to handle rescued pangolins. None of the pangolins that were rescued and sent to the zoo have survived so far. With nowhere else to go, the mother and baby pangolin were kept in the zoo for a night, and then released in Bhaktapur. After discussing the decision with zoo officials, we found no better option and hoped that the released pangolins would find their own way.

According to wildlife seizure records in Nepal, one-sixth of pangolins are captured alive. The frontline officials can only save rescued pangolins if they are able to handle them properly. Pangolins are critically endangered and the ability to rehabilitate rescued pangolins is an important need that is not currently being met in Nepal. When discussing live pangolin seizures and rescue events with frontline officials, they reported the difficulty and confusion of trying to care for a rescued pangolin. In addition, there is a lengthy legal process before releasing pangolins to the forest or handing them over to zoo officials.

There is a clear need here for a proper rescue, rehab, release plan and capacity building to deal with pangolins. The local communities, officials and even the pangolin researchers have little understanding of how to properly rehabilitate rescued pangolins. The COVID-19 pandemic and its potential connection to pangolins has added more confusion on the ground level. Knowledge of pangolin handling is essential for protecting the species and it is in our best interest to learn to deal with live pangolins safely and humanely.

When pangolins are rescued live, it is always better to release them back to the habitat if the pangolin is not severely injured. Rescue becomes much more difficult when the pangolin is not in good health. Some institutions have found ways to successfully host pangolins in captivity. For example, Nandankanan Zoo in India is successfully doing captive care and rescue of Indian pangolins, and Kadoorie Botanic Garden in Hongkong has experience in dealing with the Chinese pangolin. The exchange of experiences in handling seized pangolins can help the zoo officials and frontline authorities in pangolin range countries like Nepal where adequate knowledge and training is absent from conservation efforts.

Nepal is a source country for pangolins and is now emerging as an active international transit point for pangolin trade. Hundreds of kilograms of pangolin scales originating from the Congo in Africa and destined for China were seized in Kathmandu airport in the last few years. Nepal is becoming a new connection between Africa and China for the pangolin trade and this issue highlights the urgent need for Nepal to develop the capacity to deal with pangolin seizures and rehabilitation in the case of live rescues.

Wildlife protection laws are not enough to save pangolins. We have strong international laws barring trade and national laws that prioritize pangolin conservation action plans. In Nepal, pangolins have the status of protected species and there are stringent punishments for those who break the law – up to 15 years of imprisonment and 1 million Nepalese rupees fine - possibly the most severe punishment for any wildlife crime in the world. However, the poaching and trafficking of pangolins remains rampant.

Nepal has been wildly successful in controlling the widespread poaching of rhinos and is on its way to doubling the country’s tiger population – it’s time now to focus on the world’s most trafficked mammal, the pangolin. Nepal's capacity to develop a suitable program given their success with other megafauna has never been in question. The pangolin may not be a glamorous animal that attracts tourism money, but it is in dire need of attention and resources. We can still save pangolins from widespread exploitation and future extinction, but the time to act is now.

Kumar Paudel is Co-Founder and Director of Greenhood Nepal, a member of IUCN Pangolin Specialist Group, and a grant recipient of the Pangolin Champions Program.

Article photo: Typical Chinese pangolin habitat in Nepal © Kumar Paudel/Greenhood Nepal